Yes, of course, beauty is subjective, but does it also serve a functional purpose? I loved how Frank Wilczek at Nautilus linked beauty and science.

Does it matter to a scientist if the world is beautiful?

I don’t think science is walled off from the rest of life. So yes, it matters to me a lot whether the world is beautiful. It’s also a practical question for physicists, engineers, and designers. At the frontiers of physics, we’re dealing with realms of the very small and the very large and the very strange. Everyday experience is not a good guide and experiments can be difficult and expensive. So the source of intuition is not so much from everyday experience or from a massive accumulation of facts, but from feelings about what would give the laws of nature more inner coherence and harmony. My work has been guided by trying to make the laws more beautiful. (emphasis supplied)

The remainder of the question and answer is interesting as well. For example, the interviewer asks if the inherent unpredictability of quantum mechanics violates the Nobel laureate's ideas of beauty. Nautilus also poses this thought experiment: if birds and dogs were capable of abstract reasoning, could they, too, discover the laws of physics? Wilczek:

I think birds would be very good but dogs not so much. The dog’s world is primarily based on smell. Of course, chemical senses can support a rich life of communication and appreciation of food. You smell a madeleine and remember the past. But even if you’re very smart and have a rich social life, it’s hard to get from sensations of smell to Newton’s laws of motion and mechanics. Humans are primarily visual animals, so we have powerful ways of understanding how things move through space. We’re lucky that we can see the planets. That gives us a nice opening into astronomy and understanding gravity.

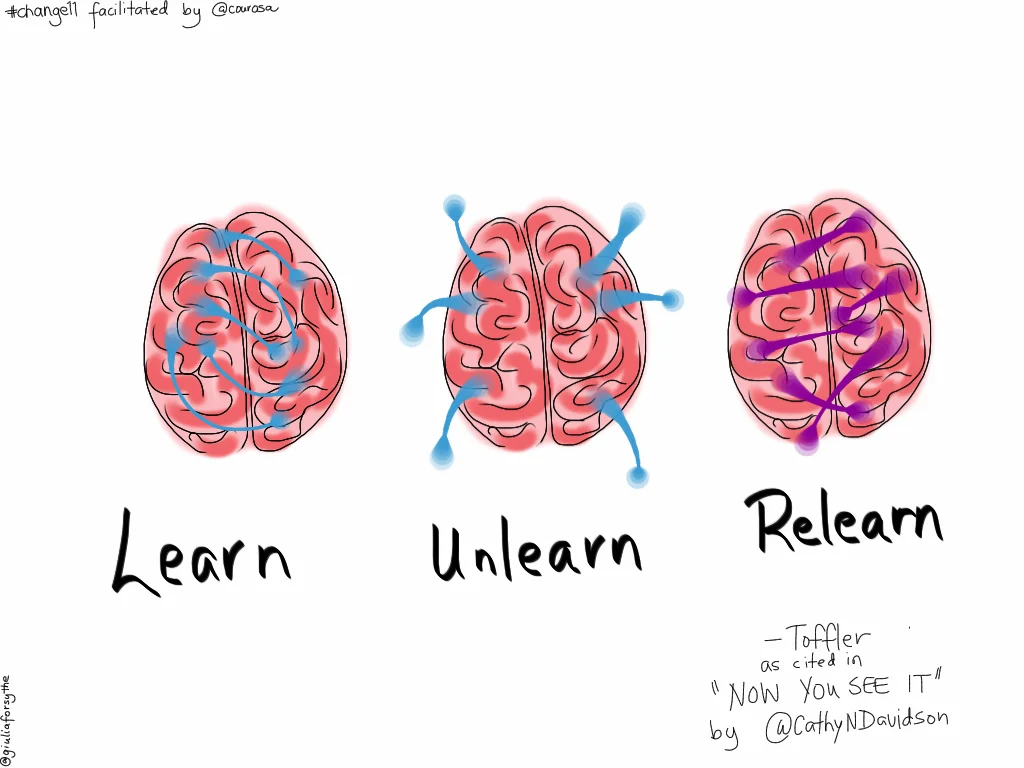

Now of course anything he might find that "give(s) the laws of nature more inner coherence and harmony" will necessarily be something we humans would understand in the first place, so the I'm not persuaded that "everyday experience" has been set aside. But the notion that (functional) beauty might be a guide to the laws of nature interests me.

Stay curious.™

Wayne